Part 2/3: How the "Internet Revolution" felt like from the inside and what we can learn for AI

How "discovering" the Internet in 1995 felt like

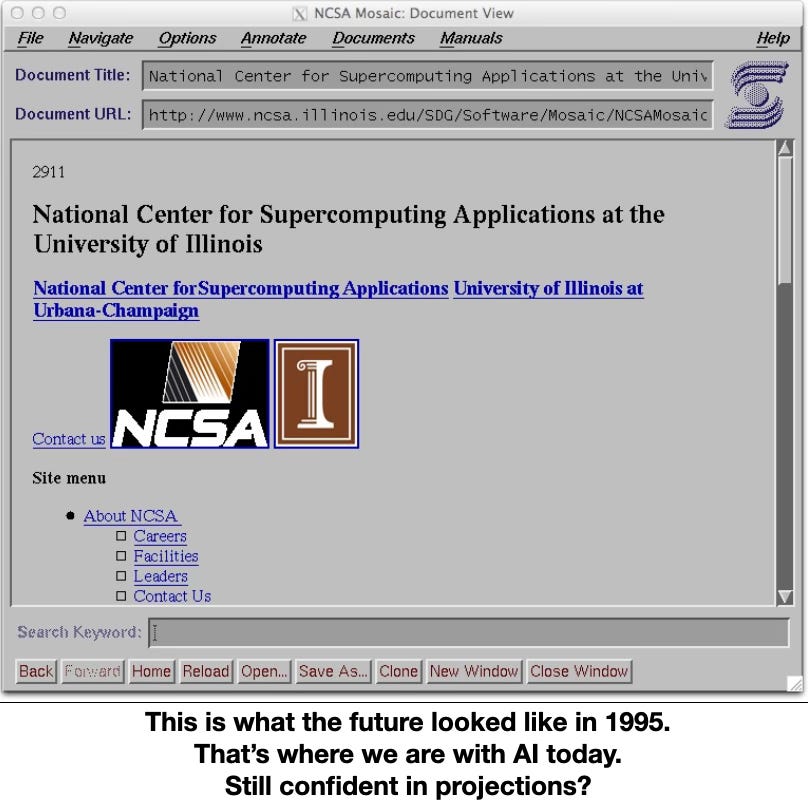

Most predictions about AI right now confuse infrastructure with value. But infrastructure revolutions always look messy, contradictory, and confusing before the value systems on top of them emerge. That’s exactly how the early internet felt in 1995 — and I was right in the middle of it.

In part 1 of this mini series, I laid out the current state on AI predictions. They not only vary wildly but often contradict each other, going in opposite directions.

That is in part due to invested interests of some actors. But it’s also because the future of AI and its impact on society is unknowable.

Yet. As the rise of AI is often compared to the last big revolution — the Internet — I reflect back on how that time felt. I was deeply involved in some pioneer work back then. My angle is subjective, but it might reveal a couple of things:

It was all done a) in the moment, and b) it took longer than you might think to go from beginnings to explosion. And: after the explosion (and after recovering from the dotcom bubble deflation), everything was different and looked so clear. It wasn’t clear at all before.

Here we go:

Time Machine → 1995, “beginning of the Internet”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The last revolution some of us might remember is the arrival of the Internet. I am old enough to vividly remember it and that might also be the reason why some of this reads like an “old man rant.”

I still remember reading a book about all the Internet protocols before HTTP. It was wild. You had finger, of course NNTP (newsgroups), WAIS for some kind of search, telnet, Archie (!), WAIS and for each of them you were required to use a different “program.” While reading the book I dreamed of an everything program that served all these protocols. What feels like a couple of nights later, HTTP (invented in ca. 1989, 1991 first implementation with a server (httpd) and a browser, 1993 Mosaic released, mid 1990s “explosion” of websites, arrival of Netscape, Amazon, Yahoo launch …)

At the time, most of us in our university institute were working on what was an early version of Siri. It was kind of successful but also practically unsatisfying. The theory worked but the limitations of “compute” at the time were so tight that it was a good demo but that’s it.

With the Internet coming around the corner, we tried to sort out more practical problems from thereon, some of them might seem absurd in hindsight, like: A project I was working on tried to solve the problem that you just don’t know what’s behind an internet link. Once clicked, what would happen? It seemed like a crazy dangerous remote control on the negative side, insane access on the positive side. Would clicking that link crash the universe, launch a nuclear bomb? Or would you rather see some fancy pic, read the latest news? Probably someone had clicked that link before you and might tell/warn you what would happen. So we built a system which enabled users to “annotate” links so that you wouldn’t be surprised. Of course this was an idea from academics for academics and it never took off.

We had no clue about how value would be created

Serendipity stepped into the room in the form of our Chinese colleague Ben-Hui who complained about the first existing search engines not indexing Chinese documents. So he built a robot system to retrieve Chinese documents. For that to go mainly after Chinese docs, another colleague built a language detection based on Markov Chains and yet another one built the indexer etc. After a while it was figured out that doing the same for German documents would actually be a good idea, given the fact that we were located in Germany. That was the FLP search engine which became flipper which became fireball. Fireball then became the springboard of a company which those involved with the first version of fireball founded (except Ben-Hui who was employee Nr. 1). It was a wild time and the people who engaged us to build the thing for Gruner & Jahr swapped over to AOL Germany. And here we were, building the whole front and backend for AOL Germany (yes, the famous Boris Becker “bin ich schon drin?”-campaign, and then as well for Netscape Germany. (We also received “Nie wieder Nachtschicht” T-Shirts as a present after successfully delivering the whole machine. We also forgot to configure the caches well, so after the press conference, the whole site went down, we switched back to the old site and then got back to our new fancy site a day later or so, well …)

Random Agent Anecdote: During that time I left that institute for another one for maybe 2–3 months and engaged in the next big hype of the time and helped build a platform for mobile agents. Something that sounded really great in theory but no one actually needed. In Berlin alone at the time there were three “startups” (that name didn’t exist yet) focusing on building mobile agent platforms. I don’t know what happened to them, but the idea died out. It basically came from the fact that Java (the programming language) had a concept of “mobility” built in that allowed you to send executable software somewhere else, have it executed and come back to you. I am just telling this because it seems that “agents” are always the second thing that comes up …)

It was the wild west. Just like today. Very few people, though, ran around with certainties. To us, the world was like a candy store. Designers turning their work from print towards the Internet built expensive “agencies” with a multiple of our daily rate — we were just dumb developers, the nerds. No one understood at all what we were doing. We were basically useful idiots in the business game. We heard that the Samwer brothers had some other people a couple of blocks further develop what would become Alando.de, the German eBay clone that eBay would eventually acquire to start eBay.de. I can’t even remember if we were asked at all to get involved, but talk in our hallways was that we were totally not interested. The Samwer’s did not speak our language to say the least and being really pragmatic dev guys, we thought simply copying something is basically very stupid and not value generating … haha.

Meanwhile companies like mobile.de and autoscout24.de (car classifieds), immoscout24.de were founded. Really simple lookup-stuff. One of them was also acquired by eBay, the other ones created their own holding structure.

Very much later, models like PayPal and Skype were created. Both acquired by eBay as well. PayPal was bought for ca. 2.5 billion. At the time a record-breaking internet acquisition and eBay was laughed at a lot for that acquisition. Especially as it failed to fulfil the promise of “connecting buyer and seller even better.” (They never even tried.) But funny enough, it was sold for a multiple. Not a great deal, but far, far from a loss.

We had no clue how work would change

I was mainly heading the development that built all the stuff for AOL / Netscape. All of a sudden I had a beautifully mixed role of leading a huge room full of developers, getting a daily call from the client’s project manager (Walter!) at 11am. “Project Manager” was one of the important titles at the time. There was no “Product Manager” or PO. (I was also years later hired into my little part of the eBay universe based on my reputation as a project manager for whatever reason. Only to get rid of the whole project management department a couple of months later.) The first book on Agile we read and that delighted us was by Kent Beck on Extreme Programming. When Scrum came around, we said it’s like XP, but for managers.

Of course it was a huge problem trying to figure out what AOL users would expect when logging in. Some things were obvious: News (one of the problems of the time was to deliver the news quicker than others. When the Concorde disaster of Flight 4590 happened in 2000, the cynical discussion in our circles was: who was technically able to deliver the news first, incl. pictures, hopefully videos and all). So, we developed a lot of gimmicks to see and test what would stick. At the time, what stuck was pretty basic: Weather, latest news, hottest news, all of that backed up with images … We tried to learn more on figuring out what people needed and little literature existed, next to “requirements engineering.” Software development wasn’t really obsessed about the user at the time.

Predictions would have been wild

OK, let me stop. Here’s the point. At the time we were simply too busy “inventing” the Internet and creating the opportunities. None of us even predicted the crash of the bubble in 2000 / 2001. We just went through it.

Yes, we were looking for ways to get closer to a customer to learn what he needs. Yes, we were surprised to meet people who had studied business and had MBAs who became our clients. But none of us saw the role of the Product Manager coming.

2008: The first books on Product Management

And, surprise, in our space, the first relevant books on the topic were certainly:

2008 - Marty Cagan: Inspired: How To Create Products Customers Love (At the same time I was working in the eBay bubble and I am quite certain that what is described was not how eBay worked. Anyhow, it was a great book and it helped us to have more classical business people and project managers accept basic principles of (even agile) Product Management, Customer Focus etc.)

2010 - Roman Pichler: Agile Product Management with Scrum: Creating Products that Customers Love. Roman also published a book before in 2007 that was on “Agile Project Management” but already with a focus on product.

Contrary to what people tell today — that Product Management was an established job or role since ages: nope. Not in our field. In hardware, in production, for sure. But we had to discover that first. Even to the point that in 2012 I was so unsatisfied with the state of Product Management education and coaching that I founded my own company in that field. We also heard reports from the bigger companies in the US that similar roles existed, that much is true.

To give you a bit of a timeline of the role of the Product Manager in software/digital contexts:

Early origins in software

• 1970s (IBM, HP, others): Roles existed that mixed product marketing and technical specification, but not yet called “product management.”

• 1980s (Microsoft): Microsoft created the Program Manager role (distinct from Project Manager) around the mid-1980s, explicitly modelled around P&G’s brand managers, but adjusted for software: PMs wrote product specs, translated customer needs, and sat between dev and marketing. By the launch of Windows 3.0 (1990), Program Managers were central at Microsoft.

• 1980s–1990s (Silicon Valley): Other software firms (Oracle, Intuit) began using “Product Manager” as a formal role, often more business/customer-focused than Microsoft’s “spec-owner” model.

Mainstreaming in digital

• Mid-1990s (U.S.): With the rise of the internet, Netscape, Yahoo, and Amazon adopted PM roles. By ~1997, “Product Manager” was becoming a recognized tech title in Silicon Valley.

• Germany / much of Europe: The role arrived later. In 1995, German software houses usually had “Projektleiter” or Produktmarketing, but not “Product Managers” in the Silicon Valley sense. The formal title/product discipline only became common in Germany around the early 2000s, spreading with the dotcom wave.

So, while the software PM role emerged in the 1980s at Microsoft as a Program Manager and spread in Silicon Valley by the 1990s, in Germany and Europe it was still mostly unknown in 1995 and the concept only became common in the 2000s, with the arrival of internet startups.

Future, hidden in plain sight

Although we were working on the things that would later work in the Internet, it had not yet crystallized for us to be sure and get a feeling of knowing.

It took a lot of serendipity and work and observing to lead us from annotations to search to content to news to e-commerce.

No one was dead sure about e-commerce becoming the thing. At least not about how huge. We had doubts. But someone had to do it. And as it was clear it had to be done, there were pioneers going onto exactly that bet. And the burst of the dotcom bubble expressed that much-needed path more clearly. For some bigger bets, it was too early. When we saw something we found most of it interesting, but there was no precedent which gave us a sense of the potential. And the potential could not be measured in the real-life analogue (eBay — classifieds).

Everything was a bet with open outcome. We also saw a lot of investment going on around us. And there was little correlation between investment and success. In fact, we saw huge investments fail and we were involved in the software development of some of those platforms, with and without success. There was no pattern.

The Push required Technological Advances

From static to dynamic web

In hindsight, though, it is clear and obvious that also some technological progress beyond infrastructure was required to provide an experience that worked for people outside of our nerd bubble.

HTTP was the basis, mass communication and ubiquity of static web pages.

Developing all sorts of use cases that make sense as static web pages.

Search, News. Everything video was still complicated, because of limited bandwidth and infrastructure. The easier things were successful at the time, because that was what worked under these conditions. What worked was mostly not a really great wild idea, but some projection of what worked in the real world, filtered through the then existing internet capabilities. Also anything classifieds, long tail, short tail, whatever dimension up and down.

A lot of things that we and others tried did not work because the idea wasn’t great but the experience sucked. When JavaScript and Ajax came around, everything changed. It started part two of the gold rush and finally the Internet Bubble was fixed again.

All of a sudden, dynamic pages enabled us to build actual applications in the browser. The stateless HTTP protocol was not limiting us anymore. The question if it makes sense to sell shoes, fashion, all sorts of things that require more of an experience, went away. As Ben Thompson of Stratechery would say, the point of integration moved from the operating system to the web browser.

Google went all crazy when they figured that out. They also solved cheaper hosting and storage. This helped them to go all in on disruption “of the margin of others”. They threw all kinds of dynamic apps like spaghetti on the wall to see what sticks. And following their philosophy that money is an unlimited resource, they gave it all they got: Free mail with a ton of free storage? No problem. Free maps, with better resolution, navigation and what have you? Disrupting the more traditional mapping services that still tried to figure out how to move to the net at all? Why not? Their own browser to become independent of MS? Google Wave, then Google Docs? Sure thing. At the time most verticals were afraid that their margin would be Google’s next chance.

I could go on and on. All I want to say is: None of this was knowable or predictable. As much as it is clear in the rear mirror.

Back to today, Back to AI predictions.

I provide all this context to explain how early we are in the journey of AI and how predictions still need to be off. The predictions are so far spread because the future is so uncertain. And it does not make a lot of sense to rely on a specific set of predictions. That angle is too narrow. What we can derive from the past, though, is what kind of acting makes sense in unpredictable times.

On the question if “will there be jobs left” it would be super soothing if just someone knew what’s coming. But no one can. The answer depends on whether AI follows the path of all big innovations until now or if it is the black swan that behaves totally differently and finally breaks the matrix.

How innovations until now always (!) created more jobs in the long run was as follows. The innovation (book printing, electricity) gets cheaper over time. Thus it becomes more accessible. This means it can be used a lot. Because of that, higher level systems can be created on top of that innovation: Light on top of electricity, super expensive in the beginning, unimaginable that the whole world would be illuminated through electricity. Books get cheaper: Knowledge and education becomes democratized, everyone gets smarter, which creates a whole new knowledge industry and finally advances in civilization. E-commerce is discovered on the top of the “Internet” and enabled by dynamic web pages.

Currently, AI is the infrastructure. The mistake that most pundits make is to confuse that with the higher level, value-creating system and predict based on AI. That’s why based on sheer opinion and imagination, the interpretation of AI’s impact is net positive and enthusiastic or net negative and dark.

Bets on value-creating systems are relatively primitive and do not solve the issues of LLMs: Connecting the LLM to search, e-commerce etc. That’s just a faster, slightly better internet. With some risks on top. Agentic systems: That’s just a couple of wild LLMs with all the built-in dangers going wild. There is not a lot of new value generated. Most is just replacement or speed up.

Maybe the value-creating system is already around and we don’t see it. Hidden in plain sight. Just like before the dotcom bubble. Maybe we only need a tiny bit of tech innovation on top, like Ajax, to get to a breakthrough.

Once the breakthrough is here it will be blazing fast, an explosion.

This concludes part two, in which I try to lay out that we are re-living 1995 and not yet post 2000. The next part will cover what to make of it. What are reasonable and responsible ways to act in such a time of uncertainty?

In 1995 we were busy building the plumbing — and had no idea what would run through it. That’s where we are with AI today.